The Giant's Dance

The stones of Salisbury

The stones of SalisburyThe ancient world rises in awe across a vast plain in southern England, where Stonehenge and two lesser known neolithic monuments carry us back thousands of years

Story by The Gazette's DONNA NEBENZAHL

The debate over Stonehenge's historic use has raged for years.

Despite a car park, visitors’ entrance and roped-off enclosure, Stonehenge and its ancient majesty can take away a visitor’s breath.

Rising from its grassy bed on the Salisbury Plain, a vast plateau in southern England, is a circle of massive stones that have held generations in thrall.

Stonehenge, a 5,000-year-old megalithic ruin, is considered the most important prehistoric monument in Britain. Despite its attendant car park, visitors' entrance and roped-off enclosure, the sight of those massive stones set against the bowl of sky made me catch my breath.

Meandering slowly around the site, I regretted not being able to reach out and touch the stones as visitors were able to do in the past. Yet I understood fully the need to keep this captivating place safe from destruction. Not far away are another, wider stone circle, at Avebury, where one can wander among the stones, and a massive neolithic mound at Silbury Hill. Debate over the historic use of Stonehenge has raged for years, but what we do know today is that the "henge," meaning earthworks, is in actuality a series of earth, timber and stone structures remodelled over a period of more than 1,400 years.

The belief that it was built by the Druids is the most recent theory to go. These marsh and forest worshippers did use Stonehenge as a temple of worship when they moved into the region, but carbon dating has shown the monument was completed more than a thousand years before the Celts inhabited the area.

People who call themselves modern Druids still congregate here, especially to mark the summer solstice. The caretakers of the site, Britain's English Heritage, allowed "managed open" access to the site last Tuesday night so worshippers could attend the sunrise.

English Heritage also will allow groups or individuals visitors to view the site privately in the off-hours, if booked well in advance.

It's easy to see why people would want to walk amid the stones. Even on a bright summer day, with dozens of other visitors and the path around the site clearly marked to prevent the stones from being touched, there is a transporting majesty in the sight of these huge stones rising from the expansive plain.

How they came there continues to mystify. The earliest portion must have been the easy part, started around 3000 BC by neolithic agrarians known as the Windmill Hill people, a semi-nomadic hunting and gathering group. They built large circular hilltop enclosures around mounds where collective burials took place, known as barrows. At Stonehenge, they built a circular bank, a ditch, and an outermost bank of about 100 metres in diameter. For the next 500 years, post holes show the addition of more timber in the centre of the monument and the northeast entrance.

Next came the Beaker people, so named because of their tradition of burying their pottery drinking cups with their dead. They invaded the Salisbury Plain around 2000 BC. Considered warlike and industrious, they are believed to be the sun worshippers who aligned Stonehenge with the summer and winter solstices.

Then around 1500 BC, the Bronze Age, the Wessex people began work on the site. One of the most advanced European cultures outside the Mediterranean, precise in their calculations and construction, they are thought to have been the ones who created the Stonehenge we see today.

Bringing stones of that magnitude to the site, especially the ones that make up what is known as the Sarsen Circle - once 30 neatly trimmed upright sandstone blocks nine metres long and weighing 45 tonnes, of which 17 now stand - remains a spectacular feat. What gives this site added dimension - it's just one of a series of stone circles in the region - is that the lintels are at least partially intact. The stones, hard-grained sandstone, were probably brought from the Marlborough Downs, about 30 kilometres to the north.

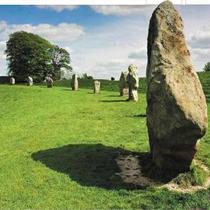

The second stone circle we visit is much rougher, less easy to decipher. But the massive site at the Wiltshire village of Avebury, 145 kilometres west of London and 30 kilometres north of Stonehenge, has often been described as more evocative of humanity's place in a mysterious world, thought to be dedicated to the themes of sexuality and the cycle of life.

The site was built by the descendants of Windmill Hill, who are also credited with creating the long barrow at West Kennet, one of the most well-preserved burial chambers in Britain, constructed around 3500 BC and in use for a thousand years.

Unlike Stonehenge, Avebury's stone circle can be walked through, and as we wandered among the massive stones, we encountered a half-dozen sheep grazing on the grassy verge. The village of Avebury, in fact, lies partly within the henge, the stones enclosing an area of 11 hectares, with two smaller circles within.

This is the largest henge in Europe, said to have delivered myriad hauntings to the village that it surrounds. Our guide, eager to show us the mystical properties of the site, offered a divining rod that moved abruptly downward for everyone who carried it as they walked slowly across the grass. Did we feel the energy of the place, he asked?

The elements of Avebury do inspire a sense of great mystery. The ditch, once nine metres deep and surrounded by a nine-metre bank, was likely filled with water to isolate the sacred temple, some say. Four causeway-entrances, one at each compass point, cut through the henge. We discovered that the bank could have been a viewing area, like a grandstand, for people from the region who attended the special rituals and ceremonies that took place there.

To create the ditch, it is said that some 120,000 cubic metres of solid chalk were dug, 60 times more material than was dug from the ditch at Stonehenge. There were originally some 400 standing stones within the henge and forming the great avenues at Avebury, though mere dozens remains. The heaviest, the Swindon Stone, weighs about 65 tonnes.

The Avebury temple was in active use for some 700 years.

The final site in our neolithic excursion is one for which no real use has been found. Silbury Hill, located just south of Avebury, is a massive artificial chalk mound with a flat top - the tallest manmade prehistoric mound in Europe, rising to a height of 39.6 metres. Carbon-dating at 2660 BC would mean Silbury Hill was created during the same period as the Giza pyramids of ancient Egypt, and, although it looks like a mound, science has revealed that it is actually a step pyramid, consisting of six six-metre high steps, then covered with earth and grass.

We viewed it from a distance, and it was easy to see why there were so many wild tales attached to the mound. One legend has it that a huge bag of earth was dropped by the devil, prevented by the high priests at Avebury from burying the town of Marlborough; another claimed it was the burial place for a great king.

While not a burial mound, Silbury might hold a larger secret: it has been revealed that it is part of a sequence of ancient sites in the area, all in alignment.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home