Cornwell Reviews "Enchantresses"

The women who cast a spell over King Arthur

review by Bernard Cornwell

KING ARTHUR’S ENCHANTRESSES

Morgan and Her Sisters in Arthurian Tradition

by Carolyne Larrington

I. B. Tauris, £18.99; 288pp

BENEATH ITS scholarly cloak, Carolyne Larrington’s new book is marvellously subversive and entertaining.

Larrington had the happy idea of concentrating on the strange and powerful women who broke the rules of King Arthur’s court and examines how they have been depicted since the earliest written versions right up to the film and comic-strip sorceresses of the present time.

Things, apparently, do go in circles. Gerald of Wales, writing in the late 12th century, said that Morgan, Arthur’s sister, was “imagined to be some kind of goddess”.

Now, in the 21st century, after a career in which she has been depicted variously as a crone, a betrayed beauty, a trickster and, usually, a nagging nuisance, she is one of the nine deities of the Goddess religion. Not a bad career recovery.

Now, in the 21st century, after a career in which she has been depicted variously as a crone, a betrayed beauty, a trickster and, usually, a nagging nuisance, she is one of the nine deities of the Goddess religion. Not a bad career recovery.

The Arthurian stories are endlessly malleable, which is part of their appeal to writers and film-makers. You want Arthur to be a Sarmation knight as he was in a recent film? Why not? The story stretches obligingly.

If he existed at all, Arthur was probably a 6th-century warlord, a Briton who fought against the Anglo-Saxons and is famously claimed to have killed 960 men in a single day.

Yet somehow over the centuries he has been transmuted into a courteous cuckold inspiring a crew of epicene knights to improbable quests. Larrington’s enchantresses go through similar changes, driven, as she demonstrates, by the concerns of the audience — which are sexual.

In the late 12th century, when the stories were first turned into poetry, the audience would largely have been the women of European courts, whose concerns were how to keep their men faithful and (often the same thing) thwart their feminine rivals.

Chivalry was their great weapon, but it was a feeble one for, when push came to shove, most knights were merciless and vicious killers. All the more need then, for women to tame them, especially in love, and the enchantresses offered an alternative source of feminine power.

Morgan’s conjuring of the Valley of False Lovers was a wonderfully condign punishment. An unfaithful knight was imprisoned for 17 years in a valley where he was forced into the company of the one he had betrayed. Think, if you will, of 17 years with a scorned Hillary Clinton and you have a measure of Morgan’s inspired malevolence.

But by the 19th century the audience had changed. Chivalry still ruled as an aspiration for Victorian gentlemen, but now the tales had become a vehicle for male “fears about the unmarried and un-controlled woman; educated, ambitious, s exual, gossipping and dangerous”.

exual, gossipping and dangerous”.

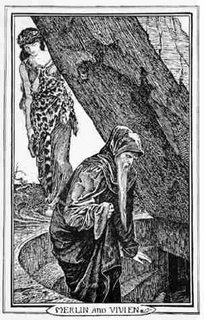

Vivien (Nimue) is the exemplar here, the serpentine young sorceress who entwines herself about Merlin to entrap him. Old man and young woman and, as Tennyson wrote on his Idylls, “what should not have been had been”.

But so much in Britain is what it should not be, and in this compelling survey Larrington discusses such strange episodes as Arthur’s unwitting incest, or his imitation of Herod in a massacre of babies. The courteous cuckold can still surprise us.

The women in King Arthur’s Enchantresses are not witches. They are manipulators, levelling the odds in a society where the highest value is alpha-male prowess. So are they now surplus to requirements in the age of equality? It seems not, for in her final chapter Larrington recounts, with a straight face, the promotion of the enchantresses to goddesses.

We are treated to the wisdom of Starhawk, one of the women responsible for the “systemisation of North America Goddess-worship”, who, in her Waxing Moon Meditation, encourages you to see Vivien as “a silver-haired girl running freely through the forest under the slim moon. She is Virgin.”

One suspects that Morgan and Vivien would have sliced off Starhawk’s head for that, because — whatever else the enchantresses were — they were not virgins and they were certainly not fools.

review by Bernard Cornwell

KING ARTHUR’S ENCHANTRESSES

Morgan and Her Sisters in Arthurian Tradition

by Carolyne Larrington

I. B. Tauris, £18.99; 288pp

BENEATH ITS scholarly cloak, Carolyne Larrington’s new book is marvellously subversive and entertaining.

Larrington had the happy idea of concentrating on the strange and powerful women who broke the rules of King Arthur’s court and examines how they have been depicted since the earliest written versions right up to the film and comic-strip sorceresses of the present time.

Things, apparently, do go in circles. Gerald of Wales, writing in the late 12th century, said that Morgan, Arthur’s sister, was “imagined to be some kind of goddess”.

Now, in the 21st century, after a career in which she has been depicted variously as a crone, a betrayed beauty, a trickster and, usually, a nagging nuisance, she is one of the nine deities of the Goddess religion. Not a bad career recovery.

Now, in the 21st century, after a career in which she has been depicted variously as a crone, a betrayed beauty, a trickster and, usually, a nagging nuisance, she is one of the nine deities of the Goddess religion. Not a bad career recovery.The Arthurian stories are endlessly malleable, which is part of their appeal to writers and film-makers. You want Arthur to be a Sarmation knight as he was in a recent film? Why not? The story stretches obligingly.

If he existed at all, Arthur was probably a 6th-century warlord, a Briton who fought against the Anglo-Saxons and is famously claimed to have killed 960 men in a single day.

Yet somehow over the centuries he has been transmuted into a courteous cuckold inspiring a crew of epicene knights to improbable quests. Larrington’s enchantresses go through similar changes, driven, as she demonstrates, by the concerns of the audience — which are sexual.

In the late 12th century, when the stories were first turned into poetry, the audience would largely have been the women of European courts, whose concerns were how to keep their men faithful and (often the same thing) thwart their feminine rivals.

Chivalry was their great weapon, but it was a feeble one for, when push came to shove, most knights were merciless and vicious killers. All the more need then, for women to tame them, especially in love, and the enchantresses offered an alternative source of feminine power.

Morgan’s conjuring of the Valley of False Lovers was a wonderfully condign punishment. An unfaithful knight was imprisoned for 17 years in a valley where he was forced into the company of the one he had betrayed. Think, if you will, of 17 years with a scorned Hillary Clinton and you have a measure of Morgan’s inspired malevolence.

But by the 19th century the audience had changed. Chivalry still ruled as an aspiration for Victorian gentlemen, but now the tales had become a vehicle for male “fears about the unmarried and un-controlled woman; educated, ambitious, s

exual, gossipping and dangerous”.

exual, gossipping and dangerous”.Vivien (Nimue) is the exemplar here, the serpentine young sorceress who entwines herself about Merlin to entrap him. Old man and young woman and, as Tennyson wrote on his Idylls, “what should not have been had been”.

But so much in Britain is what it should not be, and in this compelling survey Larrington discusses such strange episodes as Arthur’s unwitting incest, or his imitation of Herod in a massacre of babies. The courteous cuckold can still surprise us.

The women in King Arthur’s Enchantresses are not witches. They are manipulators, levelling the odds in a society where the highest value is alpha-male prowess. So are they now surplus to requirements in the age of equality? It seems not, for in her final chapter Larrington recounts, with a straight face, the promotion of the enchantresses to goddesses.

We are treated to the wisdom of Starhawk, one of the women responsible for the “systemisation of North America Goddess-worship”, who, in her Waxing Moon Meditation, encourages you to see Vivien as “a silver-haired girl running freely through the forest under the slim moon. She is Virgin.”

One suspects that Morgan and Vivien would have sliced off Starhawk’s head for that, because — whatever else the enchantresses were — they were not virgins and they were certainly not fools.

1 Comments:

I so enjoyed Mr Cornwell's Stonehenge - unfortunately, it's the only book of his that I've ever had the pleasure to read. I must correct that.

One suspects that Morgan and Vivien would have sliced off Starhawk’s head for that, because — whatever else the enchantresses were — they were not virgins and they were certainly not fools.

Had me absolutely rolling in the floor - because it's true!

Post a Comment

<< Home