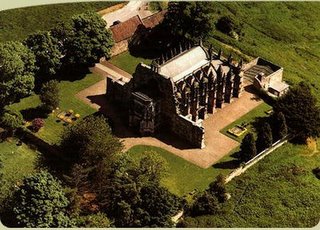

To me, it's Scotland's greatest treasure...

Rosslyn, Templars, Gypsies and the Battle of Bannockburn

Rosslyn, Templars, Gypsies and the Battle of BannockburnTHE EXPLOSION of theories concerning Rosslyn Chapel and the Knights Templar seem set to inflame debate for some time yet. With The Da Vinci Code film due out in May and new books being published regularly, the fascination with this 15th-century building seems inexhaustible.

Andrew Sinclair has written extensively about the Sinclairs and the Templars and his new book Rosslyn is in many ways a culmination of his journey to find the genesis of his now-famous surname. The book recaps old theories and offers up new ones, including an alternative version of Bannockburn that sees gypsies playing a crucial role in winning the battle.

Sinclair's interest in Rosslyn began when he rented nearby Roslin Castle for a family holiday. His cousin Niven Sinclair, who has a passion for Rosslyn, suggested he watch out for signs of Templars.

"I didn't believe a word Niven said about Templars and grails," an unconvinced Andrew says. "Then I tripped over this stone in three pieces, then looked at the roof and saw another grail symbol and thought 'Oh my God' maybe there is something. It began the whole thing."

The stone was in fact the gravemarker of a 14th-century Sir William Sinclair who died before the building of the chapel, but whose body was subsequently placed there. This Sinclair lived at the time when, according to the more prosaic interpretation of Templar history, the knights who fled France in 1304 to avoid persecution, landed in Scotland. (This colourful theory also holds that the Templars brought treasure and esoteric knowledge with them.)

Andrew Sinclair's reading of the gravemarker was that it contained Templar imagery and he concluded that Sir William had befriended the knights and become initiated into whatever secrets they may or may not have found in the Holy Land. Whatever knowledge he was given to him was passed down through the family and became enshrined in stone during the building of Rosslyn in the next century.

From this starting point the author looked into the history of his clan. In particular he wanted to know how they became so wealthy. His conclusions were that, along with possible treasure, their success lay in the early medieval arms trade – success made possible because of Templar expertise and the skill of their camp followers.

The knights were founded in 1118 to protect pilgrims in the Holy Land. In order to sustain their battle-readiness they needed a retinue of metalworkers and ironsmiths to forge and maintain their weaponry. The knights often used indigenous eastern workers - Egyptians – who may have returned to France with them after the Crusades ended.

Sinclair takes this further by suggesting that when the Templars escaped to Scotland they took these metalworkers with them. At some point these Egyptians became known colloquially as gypsies. Then in the 16th century the gypsies adopted the surname of Sinclair, which translated into Gaelic became tinkler which gave rise to their secondary naming as tinkers.

It is well documented that the Sinclairs allowed gypsies to live on their land in Midlothian at a time when they were outlawed elsewhere in Scotland. Legal papers show that a 16th-century Sir William even saved a gypsy's life from the gallows. Today a permanent exhibition at Rosslyn is devoted to this unusual relationship.

With a ready supply of skilled metalworkers plus the financial backing of the Templars, Rosslyn concludes that the Sinclairs were well placed to become the suppliers of arms and weapons to the Kings and Queens of Scotland.

Andrew Sinclair believes that the presence of gypsies in Scotland, aligned to the Knights Templar, can even be seen in one of the country's most pivotal moments.

There has long been a tradition that the Battle of Bannockburn, where in 1314 Robert the Bruce defeated the English, was won by the sudden appearance of a new contingent of fighters, said to be the townsfolk (or "small folk") brandishing pots and sticks.

Recently there has been a revisionist theory, not endorsed by historians, that argues Bruce won at Bannockburn because Templar knights fought alongside him. Andrew Sinclair certainly thinks that the knights, grateful for the protection offered to them in the face of their European-wide persecution, served the Scottish King.

"Templars may well have fought at Bannockburn - well you see one of them did - and that was William Sinclair buried in Rosslyn," says Sinclair, referring back to the owner of the gravemarker.

Although the idea that Templars fought at Bannockburn is not new, Sinclair hopes to add credibility by arguing that the presence of the Templars can be supported by the sudden appearance on the battlefield of their camp followers, who rushed out at the end to frighten the English.

"The small folk didn't bang pots and pans," says Sinclair. "I say the wee folk who came down were gypsy armourers."

This is all exciting stuff. The only problem is that by Andrew Sinclair's own admission everything relies on him having found a Templar grave at Rosslyn. Whilst he's convinced, there are many more who are not. Few historians give credence to the suggestion that Sir William Sinclair was a Templar, nor do they think that members of the order fought at Bannockburn.

However, whilst there might be little absolute proof of any connection between Templars and the Sinclairs, one thing is certain: The need to believe in something special at work in Scotland - centred in Rosslyn – means that we haven't heard the last of the mysterious knights and the Sinclairs.

3 Comments:

Bob - I need to introduce you to Paul. I dragged the poor lad away from Scotland to live here with me in the US. He could talk up a storm with you about the place. He's a big hill walker, and history buff and of course, he's homesick. I'm not even from Scotland and I'm homesick for it.

I hope to get you two together someday. Btw, I met him on the internet at The Monroe Institute's Voyager List. ;-) Small world.

Fran

That's be great. I visited Edinburgh and the surrounding area with my wife in 2000. I told her after an hour of walking the city that it felt like I had come home.

I've seen your beautiful pics from Edinburgh, and I showed them to Paul. He was happy to see a litte slice of home. He was born in Glasgow but spent lots of time on Princes Street...pub crawling. ;-)

Have you ever seen the live webcam of Edinburgh? It's kind of fun even it it's just to see the traffic. ;-)

Fran

Post a Comment

<< Home